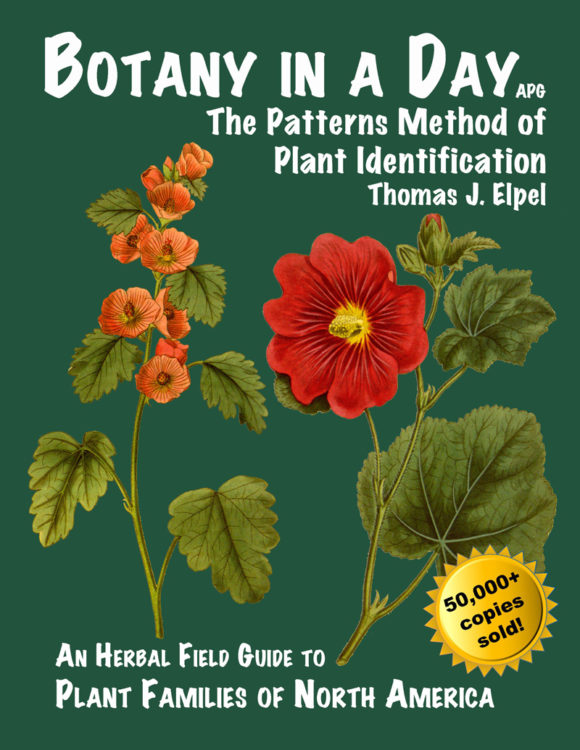

You may know Thomas Elpel best for his book, Botany in a Day: The Patterns Method of Plant Identification. Unlike traditional plant identification guides that provide descriptions and photos of individual species, his well-loved softcover tutorial, now in its sixth printing (Hops Press, 2013), illustrates key characteristics for each family and genus, helping users to arrive at conclusions about a found plant even before they know its name.

For example, if you find a weedy plant bearing 4-petaled flowers—each with 6 stamens, 2 short and 4 tall—sticking out from the flower stalk in a radial, alternating pattern that looks like a bottlebrush, there’s a good chance you’ve found a member of the Mustard family. If the seed pods can be split open from both sides, exposing a clear membrane in the middle, then you can be even more certain you’re on the right track.

Originally published in 1996, Botany in a Day is not only a useful book for the budding botanist but also for the wild edible plants enthusiast, because for each genus, where applicable, the author includes a few lines about edible and medicinal characteristics.

Originally published in 1996, Botany in a Day is not only a useful book for the budding botanist but also for the wild edible plants enthusiast, because for each genus, where applicable, the author includes a few lines about edible and medicinal characteristics.

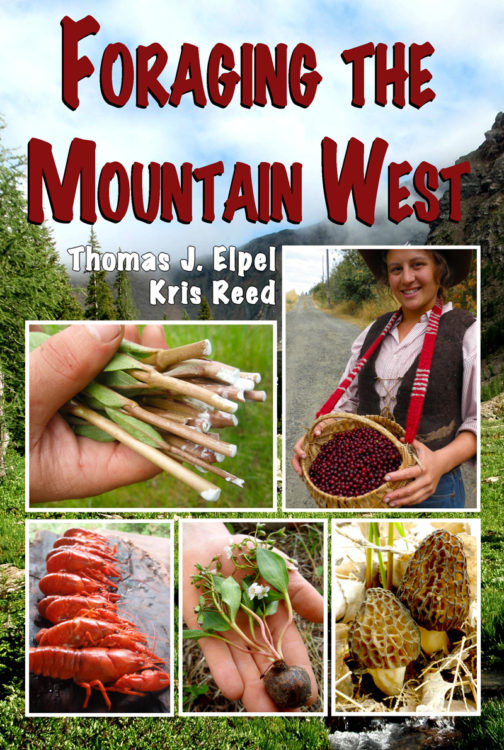

In his latest book, Foraging the Mountain West (Hops Press, 2014), Elpel and co-author Kris Reed expand on those edibility points to offer nearly 350 pages of information on wild food foraging.

Patterns Foraging

While some authors take pains to identify and write about individual wild plants at the species level, Elpel and Reed point out that this is not always necessary, if simply identifying and eating a plant is your goal.

“Learn the gooseberry-currant pattern and you will be able to recognize dozens of different species without needing to identify and name each one individually,” they explain, while still providing overviews of which species can be found where. “Patterns are not totally bulletproof, but work well enough that mistakes are usually close enough.”

We learn that not only the samaras of slippery elm (Ulmus pumila) but those of all Ulmus species are edible and “worth experimenting with,” keeping in mind that food quality may vary from species to species. Similarly, the authors write that all salsifies, cattails, clovers of the genus Trifolium, currants and gooseberries of the genus Ribes, and aggregate-type fruits like blackberries and raspberries are edible, and that the green needles from anything in the Pine family can be used for tea provided you don’t suffer from kidney problems.

By recognizing plants by group, instead of just memorizing individual species, we can find edible plants wherever we travel, even if they differ by species. At the very least, we can use the patterns method to make tentative identifications that can be confirmed by cross-referencing plants in local guidebooks.

Of course, not all plant groups lend themselves to blanket statements about edibility. Some have both edible and poisonous members—for example, the Parsley or Carrot family, which includes the deadly poisonous water hemlocks (Cicuta spp.) and poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), along with edible plants like wild and domesticated carrots. But if you know that a given family or genus has both poisonous and edible members, you know to proceed with caution after finding plants you suspect to be members of that group.

The Mountain West

Foraging the Mountain West centers on plants in a region the authors describe as “the chunk of inland geography spanning form the Rocky Mountains west to the Sierra Nevadas, then north to the Cascades and into Canada.” This is a “hardscrabble landscape” where there is too much of everything—“too hot, too cold, too windy, too wet, too dry, and too smoky,” they explain.

Elpel resides in the small town of Pony, Montana, in a home he built himself from local rocks and building materials scavenged from the industrial waste stream. Thus the epicenter of the book’s range is southern Montana, while descriptions of surrounding regions are bolstered by his and Reed’s travels.

Although here in high country Colorado we don’t have all the plants featured in the book, I was delighted to find a host of local plants about which I have been craving additional information.

Among them is brook saxifrage (Saxifraga odontoloma), a water-loving plant that bears small round leaves whose edges look like they have been carefully trimmed with pinking shears. It turns out that the authors and I share a love of tumble mustard (Sisymbrium altissimum) as well as orache, a salty goosefoot lookalike that grows in the alkali flats around Denver and surrounding plains cities. There is even a mention of arrowleaf balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata), whose young leaves are said to be edible before they unfurl, among other uses.

I find this book to be an exciting new resource of edible wild plant information for the Mountain West. The entries are longer than those found in traditional identification guides, similar in this regard to the publications of Sam Thayer and John Kallas—both of whom are generously quoted therein. I like that the book is grounded in first-hand experience, and that where the authors are uncertain of something, they state that fact.

Edible Wild Plants

Foraging the Mountain West is organized by types of food forage, with wild plants sections on salads and greens, root vegetables, seeds and nuts, and fruits. It includes a host of ideas for how to prepare various edible wild plants, from common weeds to native species.

For example, I am newly inspired to give common plaintain (Plantago major) another try after seeing the photograph of batter-dipped leaves frying in a pan over a campfire, and clovers (Trifolium spp.) after reading the inspired retelling of some of Linda Runyon’s points from The Essential Wild Food Survival Guide, among them that clovers can be combined with powdered or juiced grasses for a full protein.

“Making friends with clovers is a good way to let go of some of the stresses of the adult world and recapture a bit of lost childhood,” the authors enthuse. “Even if you don’t happen to find a four-leaf clover, at least you can make a salad.”

Indeed, salad pictures featuring immature wild strawberry leaves (Fragaria sp.) and lilac blossoms inspired me, because I have yet to use either that way. And did you know that if you harvest purslane (Portulaca oleracea) early in the morning it can contain 10 times as much malic acid than it does in late afternoon, owing to metabolic processes that help it adapt to desert environments? So if you want tangy purslane—go foraging at the crack of dawn!

For winter greens, they recommend watercress (Nasturtium officinale), brooklime (Veronica americana), monkey flower (Mimulus spp.), and chickweed (Stellaria media). There are also entries on sow thistle, dandelions, stinging nettles, goosefoots, docks, violets, thistles, and prickly pear cactus, to name a few more in the salads and greens chapter.

Getting at the Roots

Foraging the Mountain West also contains an extensive unit on wild root vegetables, a must-read for any Rocky Mountain survivalist eager to know her wild starches, which are essential for long-term wilderness survival.

One of the plants discussed is the blue-flowering common camas (Camassia quamash). I have yet to find this plant in my travels, but they describe it as so plentiful in some areas as to trick the eye into seeing a high mountain lake when the flowers are in bloom. Common camas roots are indigestible raw, fermenting in the gut to cause “prodigious flatulence” unless long-cooked to convert their inulin to fructose. The authors explain how native folks steamed them overnight in grass-filled pits, with hot coals at the bottom and a fire overtop, and they include instructions on how to do this yourself in the field.

Other featured “root” vegetables include glacier lilies, yellowbells or fritillaries, sego or mariposa lilies, burdock, yampa, harebells, spring beauties, onions, and biscuitrooot, to name a few, along with minor mentions of evening primrose, arrowhead or wapato, and bistort.

similarly cultivate spring beauties?

Some of these plants are no longer regionally abundant where the march of progress has overtaken sensitive habitats, so in such cases the authors encourage a “caretaker attitude.” This is distinct from the view that it is only sustainable to take a specific percentage of a plant colony, a perspective they decry as “wrong framing” because it views humans (not to mention bears) as pillagers, and nature as finite—neither of which they think are the case. Some plants even benefit from ground disturbance caused by the digging of vegetables, they point out, whether by human hand or grizzly paw. “Being a caretaker can be as simple as eating wild fruits and crapping in the woods like a bear,” they write.

Still, they advise harvesting root vegetables only where a plant is locally abundant, and in some cases, only as a curiosity or survival food rather than regular practice. “Given that a single tuber may be several years old, and it can take dozens of them to make a meal, conservation is a critical concern,” they writes of spring beauties (Claytonia lanceolata), which are edible from tuber to flower.

“When harvesting spring beauties, I am reminded that potatoes were similarly small at one time, and that modern potatoes were created through hybridization, breeding, and manual selection to enlarge the size of the tubers,” Elpel reflects. “I sometimes wonder if a similar miracle could be achieved by crossbreeding and cultivating the various species of Claytonia.”

Poison by Degree

The book includes discussion of poisonous plants in red text in each unit’s “Edible or Poisonous?” section, making concerns easy to navigate.

Roots merit particular attention, they point out, because “the percentage of poisonous starchy roots is relatively high” due to the fact that “the total number of starchy roots is so low.” Still, toxins tend to be more concentrated in the starchy roots than vegetation, they note, so “consuming the wrong root could have serious consequences.”

Since the leaves of white-flowering mountain death camas (Anticlea elegans syn. Zigadenus elegans), a poisonous plant, resemble those of blue-flowering common camas, they recommend harvesting the latter while it is in flower, and not eating any bulbs whose tops break off in the digging lest you accidentally eat the wrong one. “According to some reports, entire Indian families were killed when a single bulb was mistakenly added to the stew. However other reports suggest a person would have to ingest several bulbs to get a lethal dose,” they write, concluding that “the potency probably varies between species and locations.”

Other plants are less toxic, even though they might make a person sick. For example, our native lupines (Lupinus spp.) contain only “mildly toxic alkaloids,” whereas some European species even have edible peas. “Nothing in the Pea family is drop-dead poisonous,” they write. “Although there are many ‘poisonous’ plants that could make a person sick, it would take some effort to successfully kill oneself with anything in the Pea family.”

Fruits & Berries, Nuts & Seeds

Fruits and berries, nuts and seeds also fall into the domain of the aspiring survivalist, since they offer sugars, proteins, and oils.

Foraging the Mountain West includes entries on huckleberries and blueberries; salal and related Gaultherias; strawberries; raspberries, blackberries, salmonberries and other aggregate-type fruits; rose hips; wild plums; chokecherries and urban-foraged nanking cherries; feral apricots; serviceberries; black hawthorn; and apples and crabapples, to name just a few. Suggestions for drying your wild-foraged fruit include racks above the wood stove and rolling up the car windows with fruit inside for “a great solar-powered food dehydrator.”

“Virtually all blue berries are edible, and the majority of red berries are edible, but most white berries are not,” the authors write, in the spirit of grouping plants, while other wild food writers eschew such generalizations. They also include descriptions of bad-tasting, mildly toxic, and very poisonous berries.

“Got cabin fever? Try harvesting crab apples and making jelly in mid-winter!” they exclaim in the Malus entry. So convinced was I that I grabbed a handful off a tree in Breckenridge in February and started gnawing on their tart, mushy flesh. They were pretty good. Elpel and Reed suggest using the mushy ones for fruit leather, and comment that “skills such as this could be vital in the event of a civil disaster.” Meanwhile, in landscaping our yards, they ask us to “keep the neighborhood children in mind, and plant fruit trees along a front sidewalk to cultivate the next generation of foragers.”

There are good chapters on pine nuts—which get surprisingly little coverage in the wild food literature—and non-native black walnuts, along with an essay on the domestication of grasses into corn and other cereal grains.

“Seeds and nuts are packed with proteins and oils that are essential for survival,” they write. “Fortunately there are about a thousand trees, shrubs, herbs, and grasses with edible seeds or nuts in the Mountain West. Unfortunately, almost all of them are either too small or scarce to economically harvest in any quantity.”

After reviewing the various types of seeds—including those of mustards, Parsley family members, sedges, mints, buckwheats, and peas—they give accounts of wild sunflowers, amaranth, and grasses. Virtually all grasses are edible, they explain, with the exception of darnel ryegrass (Lolium temeluntum), or grains infected with ergot fungi, which appears as black, powdery growths. The grasses they have found most useful, after first separating the seeds from the chaff, include reed canary grass (Phalaris), indian rice grass (Oryzopsis), and timothy grass (Phleum).

For a botany tip to distinguish grasses, rushes, and sedges, they share this fun little ditty: “Sedges have edges. Rushes are round. Grasses have joints when the cops aren’t around.”

Traveling for Resources

Thomas Elpel was interested in living off the land from a young age, inspired by early visits with his grandmother who lived up Granite Creek near Virginia City in southwest Montana. She didn’t have a television or radio reception, and she made a practice of harvesting roadkill and learning about edible and medicinal plants.

“From reading survival books, particularly Tom Brown’s, I thought that a person should be able to survive and prosper anywhere,” Elpel writes of his early interest. “Brown implied that nature was like a banquet where a person could go out and feast. I was inspired to hone my skills until I could walk out the door with only a knife—or perhaps without it—and find everything in nature I needed to survive.”

But foraging proved to be the most difficult of the survival skills, because he found he couldn’t get a lot of food in return for the amount of time he invested. He conducted timed studies to quantify the results, and found them dismal. The experience led him to an important conclusion—that the Tobacco Root Mountains, with their dry soil of crumbled granite, made for poor wild edibles, smaller and less abundant than those even a short distance away.

“Western tribes were nomadic for a reason,” he concludes. “I discovered that nature truly is like a banquet, but in the West, the table is very long, and you have to be at the right place at the right time.”

Once an idealistic young survivalist, Elpel is now a more practical middle-aged man. “Oddly, I feel more native to the Rockies more now than ever, having dropped my beliefs and accepted the reality of it,” he writes. “Fifty-thousand acres is not enough to survive on when the worthwhile crops are growing in another mountain range three hundred miles away!” Instead, he explains: “Here in the West, native peoples kept a mental map of what grew where and when it was in season, migrating hundreds of miles, sometimes more than a thousand miles, over the course of a year. In that spirit, I too have developed a mental map of food resources spanning several states.”

This struck a chord with me because I’ve come to do the same—maybe not traveling hundreds of miles, but definitely stopping and checking a growing list of locations when I happen to be traveling through a region. I know of feral asparagus, milkweed, and orache in a Fort Collins field, pine nuts in the pinyon-juniper forests south of me, and fat huckleberries and serviceberries on the Western Slope, not to mention feral apples, pears, plums, cherries and apricots in our region’s former farmlands.

But I am envious that Thomas Elpel even has favorite places to pick oranges, lemons, and dates. Wild-foraged citrus and dates? Swoon.

Modern Hunter Scavenger

Elpel and Reed take the concept of free food beyond wild plants in Foraging the Mountain West, including chapters on how to scavenge and process roadkill, identify edible mushrooms, dumpster dive for discarded dinners, and hunt small game with sticks, rocks, and spears. Their missions take them deep into wild spaces to live off the land for extended periods of time, but also include foraging feral fruits and vegetables from urban landscapes, or stepping past the occasional “No Trespassing” sign for an elusive morel.

Invasive species eaters will appreciate the chapter on carp—which though “esteemed as a traditional Christmas Eve dinner in central Europe” and a good source of food, is generally disdained as a “trash fish” or “bottom feeder” here in the U.S. There is also a chapter on crayfish as inland seafood.

“It is my hope that you the reader can benefit from this book to become more native to this place,” the authors conclude, “not as some romantic idea of the past, but as we know it today.”

A version of this story appeared in the February 2015 edition of the Wild Edible Notebook. Find Thomas Elpel online at http://wildflowers-and-weeds.com.

Loved reading this book review! I can’t wait to get a copy of this book. Sounds like it will inspire many fun adventures.

Thanks!!

Andrea

So far, my foraging subsists on getting dandelions for my pet rabbits consumption. I pick the wild dandelion from mid-April to mid-November. In Winter i buy the italian versions, readily available.

And I cut any wildwood from Sugar Maple trees. Also harvest any woods brought down by city vehicles where the personnel are not careful. I have a 3-yr old Cottontail Rabbit and raising as a pet. He is not an eatable. The gathering in the summer saves a lot of money for us. And exercise for me.

It’s funny, I understand, I spent a lot of time foraging for my goats a few years ago:)