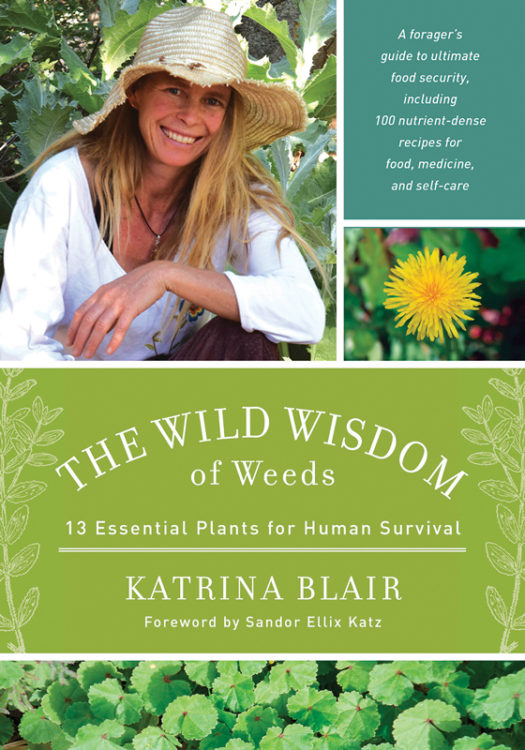

Perhaps the hot springs had something to do with it, but when I sat down to review Katrina Blair’s book, The Wild Wisdom of Weeds: 13 Essential Plants for Human Survival (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2014), I found myself enjoying a sort of inner peace.

Perhaps the hot springs had something to do with it, but when I sat down to review Katrina Blair’s book, The Wild Wisdom of Weeds: 13 Essential Plants for Human Survival (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2014), I found myself enjoying a sort of inner peace.

The book features chapters on 13 edible, medicinal, and useful plants, found worldwide, that are widely considered “weeds.” These include amaranth, chickweed, clover, dandelion, dock, grass, prostrate knotweed, lambs’ quarters, mallow, mustard, plantain, purslane, and thistle. Blair travels abroad often to speak on wild plants, and she chose the 13 because she come across them regularly in her travels.

She considers them to be “essential plants for human survival,” not from a survivalist perspective, but because they are abundant, free to harvest, and readily available to people around the world. Also, she writes that these plants contain “exceptional nutrient density,” and “offer a host of attributes that provide simple solutions to many of the basic requirements that we need to live in a prime state of health.” The book teaches how to make use of the 13 plants for food, medicine, and even self-care products like lotions and shampoo.

A lifelong lover of plants, Blair earned a graduate degree in holistic health education from John F. Kennedy University in California. In 2009 she published a book of wild, raw, and living foods recipes entitled Local Wild Life: Turtle Lake Refuge Recipes for Living Deep.

A lifelong lover of plants, Blair earned a graduate degree in holistic health education from John F. Kennedy University in California. In 2009 she published a book of wild, raw, and living foods recipes entitled Local Wild Life: Turtle Lake Refuge Recipes for Living Deep.

In The Wild Wisdom of Weeds (2014), she takes her ideas a step further, promoting a way of life while delving deep into the 13 featured plants. She encourages self-reliance by having us utilize the local abundance around us, and describes the book as “a journey about remembering our identity, rooted in the wisdom of our indigenous ancestors, while living in today’s modern civilization.”

The Wild Weeds

Each of the “wild weeds,” as Blair refers to them, is featured in its own chapter in the second part of the book, starting with a description of the plant along with a list of related useful species. Although she gives species-level scientific names for each, she includes broader, genus-level and in some cases family-level, discussion of related plants in her accounts. For example, the “Mustard” chapter is headed with the binomial Brassica juncea, but the chapter itself includes a broad discussion of many mustard species and genera.

The plant accounts are interesting and more in-depth than a traditional field guide allows, since an entire chapter is dedicated to each one. There are sections on edible and medicinal uses, and another section dedicated to “current uses” in which Blair relates how she and the folks at Turtle Lake Refuge make use of the plant. Her accounts speak to many years of first-hand experience working with these plants, and are bolstered by research cited by chapter in the reference list.

A major theme of the book is global plant use, so she includes a list of global names for each plant. In each chapter’s history section, there is a review of both historical and current plant uses that I found very interesting. For example, she writes how in Lapland the Sami people use dock greens as a rennet substitute to make buttermilk and cheese, and how in Syria, a dish called khebbese is made with mallow greens, bulgar wheat, olive oil, and onions.

Each chapter concludes with recipes, many of which are for raw food, in keeping with the author’s belief in the nutritional power of living foods. There’s thistle lemonade made with thistle greens, sprouted amaranth alegria bars, dandelion spicy chai tea, and even a dandelion ice cream made with dandelion greens, avocados, lemon, water, and honey. Many of the recipes for crackers, breads, or snack bars are done via dehydrator or sunlight instead of the oven and make use of freshly sprouted, cultivated ingredients combined with wild foods. I’m not a raw foodie myself so the recipes surprised me—which is great, because I am always on the lookout for new ways to prepare wild foods. There are more than 100 recipes in all.

In addition, Blair offers detailed instructions on how to make healthy green powders from dehydrated greens that can be added to winter meals and smoothies, explaining that we can replace store-bought vitamins and minerals with those gleaned from wild plants. She includes a wild weeds supplement chart indicating which of the 13 plants are best for calcium, vitamin E, antidepressants, and omega-3’s, to name a few, as well as a plant-by-plant discussion of properties and proportions.

What Turtles Do

The Colorado-based Blair is a pacifist and a lover of all living things. She is an adventurer who makes lengthy high altitude journeys on foot without food, water, or filtration device, feasting not only on the land but on gratitude—a story she relates in the Wild Intelligence chapter. She is an advocate of deep ecology and permaculture. The one time I attended a wild food hike with her, she conducted it barefoot, her long golden hair flowing, a bright smile on her face.

While the second part of the book is dedicated to the 13 plants, the first part is unlike many plant guides in that it centers on the author’s story and worldview, and contains a spiritual or philosophical bent.

We learn how Blair and friends started Turtle Lake Refuge in 1998 while working to preserve 60 acres of local wetlands, raising awareness by serving locally grown, wild, and “living food” lunches. Now, the group has a town location in Durango, where two days a week they serve lunches featuring locally grown, wild-harvested, and living foods. There is also an organic community farm at Turtle Lake Refuge, a 2-acre plot located 4 miles outside of town, where in addition to cultivated crops the “Turtles” harvest wild plants when they are in season.

Thus the story is part farm log, for it tells not only of wild plants, but of a way of life that incorporates both wild and homegrown, living raw foods into a lifestyle.

Community Activism

Community Activism

The first part of the book also features a retelling of community activism projects undertaken by Blair and her group, including a lengthy battle for herbicide and pesticide-free parks in Durango. It began with the “Dandelion Brigade,” a group that would harvest dandelions organically for homeowners, and afterwards make dandelion lemonade using a bicycle-powered blender, sharing the lemonade around in the hopes of engendering love for the much maligned plant.

Letters to local newspapers followed, along with presentations at city council meetings. This led to the creation of two chemical-free parks. Next, the group gathered signatures for a ballot initiative, which ultimately led to the passage of an ordinance to create an organic land management plan for Durango public spaces.

“As a beekeeper and a lover of life, I find it of critical importance that we make the necessary changes immediately to start creating an ecosystem that will sustain pollinator immune systems!” she writes.

Even as she fights to change her town’s practices, however, Blair practices “unconditional love” with her neighbors who spray herbicides for a living. “Encouraging tolerance for all life is an important state of mind to cultivate within our community and ourselves,” she explains.

A Lover of Invasive Species

This love for living things extends to so-called “invasive weeds,” a term she argues is unfairly pejorative. Discovering the 13 plants around the world, in proximity to human settlement, affirmed for her that they belonged there. “They were not deserving of the derogatory names often given to them such as ‘invasive,’ ‘non-native,’ ‘aliens,’ ‘noxious,’ and ‘aggressive invader species,’” she writes. “I hope to shift the perspective that views them as the bane of society—thereby justifying their eradication. They belong on this planet just as much as everyone else does and require the same attitude of tolerance that we are cultivating for all beings in our attempt toward world peace.”

She believes that the concept of “invasive” is flawed, since it depends on an “arbitrary decision of timing” regarding when a particular species arrived in a region. “It is important to remember that ‘native’ habitat only represents a moment in time,” she writes, expressing concern that our efforts to control non-native species with petrochemical herbicides do more harm than good. “The weeds themselves are actually filled with light, the sun’s light that has been transformed into green chlorophyll,” she writes. But there is also a dark side—“how they are discriminated against as a life-form in some circles of our civilization.”

Instead Blair encourages acceptance that nature is doing what nature needs to do, and that the “wild weeds” are part of that. “The secret of life in Taoist perspective is to return to the ‘primitive chaos-order’ of the Tao,” she writes. “The wild weeds are examples of nature’s creative edge. They lead the way of the new frontier that is constantly forming.”

Embracing the Magic

As might be expected from the title, there’s an element of magic to The Wild Wisdom of Weeds, starting with the creation myth the author penned for the preface. In it, the Great Spider laments how humans have drifted away from wild plants, but later sings songs of elation when they rediscover the wild abundance around them. There are also poems, wild plant raps, and whimsical drawings throughout.

In one chapter, Blair shares instructions for a biodynamic weed remedy to use in case we absolutely must get rid of our weeds—for example, if it is required by a homeowners’ association. The remedy, based on the homeopathic principle of “like cures like,” involves burning weed seeds and shaking the resultant ash with water a specific number of times, ideally on the waxing moon or in the moon of Leo, before applying it to the ground.

Elements such as these provide a window into the author’s worldview—a spiritual orientation or belief system that permeates the book. Whereas the plant accounts are organized around first-hand information and research, other aspects might make science-minded readers uncomfortable. And yet, the living food, love-all-creatures, celebrate-wild-abundance lifestyle Blair exemplifies might intrigue others. So I suppose it depends on your orientation.

As for me, I love eating wild plants. I’m not sure whether or not, when I ingest their “primal essence of life,” I feel the “deeper sense of wholeness, confidence and self-reliance,” that Blair talks about in The Wild Wisdom of Weeds. But I like the idea that self-reliance, and connection with the natural world, can be strengthened by making use of the natural resources around us. I’m even inclined to like the notion that when we eat wild plants, “our vibrational spin increases in steadiness and speed, inspiring a life of simple happiness and clarity.” So maybe that’s why I was feeling so happy and peaceful that day I sat at Strawberry Park Hot Springs reading the book.

No matter where you stand on science and religion, however, there is plenty to be gleaned from The Wild Wisdom of Weeds about 13 of the world’s most common useful plants—those which can be found growing in proximity to human settlement worldwide, and perhaps even at your doorstep.

I bought Katrina’s book last year and really like how she organized it for us to learn from. I had a big plate of Pursalin for dinner tonight and made a poultice from plantain to help my skin heal after skin cancer surgery thanks to this book.

Hi there, I got a recipe from Ms Blair’s book off of this website https://www.chelseagreen.com/2020/grow-sprouts-winter/

I am trying to find out how to make this recipe. From understanding whether “sprouted” here means soaked or truly sprouting tails. And how to get tails without rotting (it’s so hard to get all the water off after rinsing the fine seeds) but more importantly, the recipe doesn’t explain the “how to” around shaping into bars. I find the mix can’t be shaped into anything because it doesn’t stick together. The only sticking us all the little seeds to my hands.

Can you advise?

Hi Rachel, I don’t know Katrina’s recipes in enough depth to answer but I think you can reach her here: http://www.turtlelakerefuge.org. Sincerely, erica

Is there any reason you might never try just cutting a good size handful or two of the weeds that just come up in my back yard (i had a picture to show you but couldnt find youractual email to attach it) , wash them , blend them in water, hold my nose and just hammer it down? I mean there’s not usually anything poisonous is there? I downloaded your book but didnt have time to read it very closely. I thought it might be quicker to cut and drink while i read.

Hi Gloria, sometimes poisonous things grow in lawns. It is best to identify and learn each plant you are eating. My apologies but I don’t have a finished book yet! Maybe you are thinking of someone else?