On Saturday I stopped by my sister-in-law’s house, where I was persuaded to help weed her hillside of invasive nodding thistles (Carduus nutans). I didn’t mind because several days of rain have left the ground soft with moisture, and nodding thistle happens to be a good wild edible—one whose tender flower stalks I am always happy to forage if I find myself in the right place at the right time.

Edible thistles

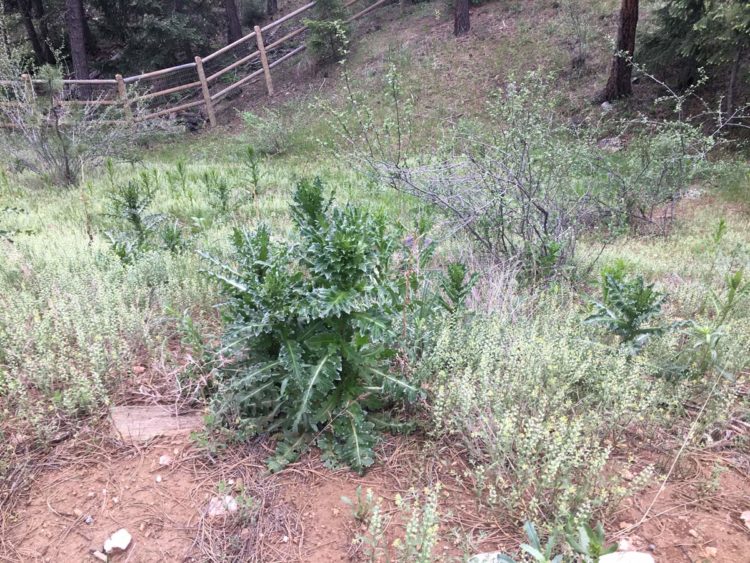

As a group, thistles of the genus Cirsium as well as the nodding thistle (Carduus nutans) are edible, although they vary in palatability, as Samuel Thayer writes in The Forager’s Harvest (2006). They are recognizable by their irregular and often pinnately divided, deeply lobed leaves, which have sharp prickles at the point of each lobe, and can grow to heights towering over your head. Thistles have composite flower heads made up primarily of disk florets, which are often pink-purple and sometimes white in color.

They have several edible parts—the taproot, best foraged from basal rosettes without a flower stalk; the leaves and midribs if you remove the spines; and the fast-growing young flowering stalks. My favorite part of nodding thistle is the young flower stalk after it has just shot skyward, while it is still tender enough to bend, before the reproductive parts develop. This was the stage at which I found it on Saturday at my sister-in-law’s house, which is located at 7,800 feet in the Lookout Mountain area of Colorado.

I mention the elevation because it makes a difference in timing your harvest. In Colorado, May is generally the month for nodding thistle stalks at lower elevations; May/June is good for the middle elevations; and June at higher elevations. Similarly, as you head south, the season tends to be earlier; as you head north, it is later. These elevation and longitudinal observations can provide general guidelines to help foragers time their wild harvests, although some variation is to be expected based on other factors like rainfall, temperature, and growing conditions.

Nodding thistle is easiest to distinguish from other thistles at younger stages by its leaf margins, which have a whitish to purplish tinge or blush along them. It grows a thick flower stem, with spine-tipped leaf material running along it in wings. Later, it develops the nodding flower head for which its common name was bestowed.

Inedible non-thistles

There are a couple of plants in the West that might be superficially confused with thistles.

Our native prickly poppies (genus Argemone) of lower and middle elevations are also spiny and thistle-like in appearance, with white tinges on the leaves. These are easy to distinguish when in flower, as they make large, showy white flowers with large petals and yellow centers, followed by prickly, egg-shaped fruits. In contrast, thistles generally have purple composite flower heads, subtended by overlapping bracts that give the buds an artichoke-like appearance, followed by fluffy seed heads.

Of course if you want to harvest nodding thistle flower stalks before the reproductive parts appear, note that nodding thistle stems are thicker and greener than the whitish prickly poppy stalks. Also, prickly poppy leaves have white tinges along the midvein and side veins, whereas nodding thistles have the white tinge along the leaf margins. You can also look for the tall, dead, nodding flower stalks of the previous year’s thistle growth as an indicator you are in a nodding thistle patch. Prickly poppy parts are reported to have medicinal uses but the plant is generally not considered edible.

The teasels (Dipsacus species) also bear some resemblance to thistles, and confounding matters further, a friend of mine once referred to teasel as “a thistle”—a confusion of common names that might mislead some. Teasels are tall, weedy plants found in the West’s lower elevations that produce a prickly, cone-shaped flower head used for “teasing.” Unlike most thistles, the basal leaves of common teasel (C. fullonum) have scalloped but not deeply lobed margins, making them more readily confused with horseradish than a thistle! More like thistles, the basal leaves of cutleaf teasel (C. laciniatus) are deeply lobed, but they lack the prickles along the leaf margins that thistles have. Teasel is not considered an edible plant.

Collecting and eating nodding thistle stalks

As I weeded that hillside Saturday (with gloves!), I took note of which nodding thistles had the thickest flower stalks, broke those off at the bend point, stripped the leaves off, and added the stalks to my pile of keepers. Next, I used a knife to strip off the remaining leaf material, attached prickers, and tougher outer skin layer.

The result is a thick, substantial vegetable, like celery but better, perhaps with a hint of artichoke—to which, incidentally, thistles are related. These can be eaten as is, dipped in creamy salad dressing, chopped raw into tuna or chicken salads, boiled and salted as a side dish, added to soups—you name it.

I’ll leave the rest up to you. Happy weeding and eating!

Updated 2.22.21

This is great, I was nurturing some thistles near my water tank, unfortunately I didn’t tell my sister and she sprayed them!

I’m sure you’ll find more elsewhere!