Foraging prickly lettuce is an art, and one I look forward to each spring, ever since the day I graduated from beat-up, bitter rosettes to the tender carpets of young lettuce greens found in fields and old agricultural places on the plains.

An introduced Eurasian species, prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola) is found throughout the United States and Canada. It is distinctive in its mature form, with leaves that turn to face sideways, sometimes pointing east and west, Euell Gibbons relates in Stalking the Faraway Places (1973). Prickly lettuce leaves twist to optimize exposure to the sunlight, Sam Thayer explains in Nature’s Garden (2010); the result is a plant that looks as if it “has been pressed between two pieces of plywood.”

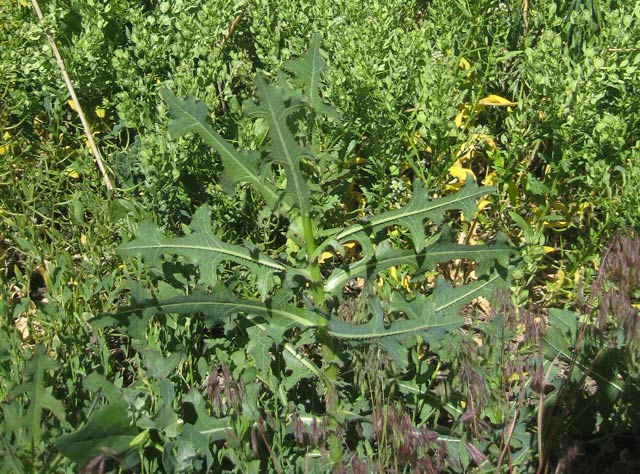

Mature prickly lettuce has a solid stem with deeply lobed, alternate, clasping leaves. In contrast, the margins of young leaves can have few or shallow lobes. Prickly lettuce buds and flowers are numerous, borne in a panicle or branched cluster of beaked buds that open into small, yellow ray flowers like tiny dandelions. Later, the seedheads look a bit like dry, dandelion seed puffs.

I’d chased edible wild plants for years before paying much attention to prickly lettuce. I knew from the guidebooks that it was edible—but also that it possessed an extremely bitter latex coursing through stems and petioles and covering the mature leaves. Furthermore, as it bears thin, needle-like bristles on the leaf margins and midveins, I figured it would probably not be very fun to eat.

Some years back I tasted a mature leaf despite my misgivings at Colorado forager Cattail Bob Seebeck’s house, only to discover that it was indeed too bitter to eat. Still, a forager in Colorado is a desperate forager indeed, for her warm seasons are short and the pickings slim compared to other regions.

So one spring, hungry for green forage in April, I experienced a brief love affair with the scraggly yard rosettes of prickly lettuce in Gregg’s parents’ backyard in Aurora on Denver’s outskirts. It was early enough in spring that they had not yet sprayed the unwanted Asteraceae with yard poisons, so they invited me to scavenge what I could.

The specimens were still in their young, spring rosette forms, but the latex in the dandelion-like leaves and small prickles in a line along the midvein on the underside of the leaf helped to confirm that I’d found prickly lettuce.

In the youngest specimens, however, I had to cut and squeeze the midveins well in order to spy just a hint of the latex, which becomes more obvious as the plant matures.

I rinsed and chopped and tasted one. The prickles had not yet firmed up enough to be bothersome, and the flavor was far less offensive than the mature plant I’d tried, though it was still bitter like a dandelion. This makes sense because prickly lettuce is closely related to dandelions.

Despite the modern aversion to bitter foods, this milky juice is valuable as a digestive aid and spring tonic, useful for cleansing the liver after a long winter of eating hard-to-digest foods, Elpel writes in Botany in a Day (2013 ed.). So the fact that young prickly lettuce is a touch bitter can be considered a good thing—both for those who enjoy bitter greens like endive, and for those who relish tapping into the wisdom of our refrigeratorless forbears who enjoyed annual health benefits from the bitter greens of spring.

Cultivating the Wild

Interestingly, our modern lettuces—like iceberg, Romaine, butter, green leaf lettuce, and stem lettuce or celtuce—are cultivars of Lactuca sativa, thought to have been bred from prickly lettuce thousands of years ago in Egypt.

To this day, prickly lettuce hybridizes with cultivated lettuces, though the resultant seeds from interbreeding apparently produce tough, bitter leaves. The good news is that because of its interest in cross-breeding, prickly lettuce can help diversify the gene pool, protecting lettuces in perpetuity.

Forager on a Bed of Lettuce

Around the same time I was experimenting with my first scraggly lettuce rosettes in Aurora, I started noticing lush patches of a young green I did not know. I photographed and wondered about these lovely patches, only to later discover that they, too, were prickly lettuce—just growing under different conditions than the tough, solitary invaders of my father-in-law’s carefully tended landscape.

Once I made the connection I started picking light green rosettes where the leaves looked healthiest—some from forested areas with dappled sunlight and others from open fields in direct sunlight.

Back at the house, I swirled the leaves in a bowl of cold water to refresh them. Because some of the greens I collected were a little too close to a dog-walking zone for comfort, I soaked them in a water-and-vinegar bath in the hopes of killing any unwanted microbes.

Those spring lettuce greens went a long way into dinner salads, pack-along salads, and spring rolls, but the lettuce beds turned out to be the gift that kept on giving, reawakening again in fall for another round of picking. My friend Butter wrote to tell me about it. Since they were still going strong in late November that year, I headed down for a final wild food mission of the season. We got prickly wild lettuce and prickly pears on those last few sunny days before the weather changed and my world turned white once more.

In retrospect it’s funny to have spurned a plant for so many years, only to be suddenly reawakened to its merits. As my joy over prickly lettuce grows with each new epiphany, I find myself eagerly awaiting those small miracles still in store. Prickly lettuce seems a fitting way to put foraging to bed each season, and to welcome spring once more.

UPDATED 4.28.20

Just last night, I made a tincture of prickly lettuce for the first time.

An excellent post that showed me that I was right about that weed being related to lettuce! I live in Tasmania, Australia and kept seeing these plants with lettuce like seed and told my husband it had to be related to lettuce in some way. Cheers for clearing that up and for showing me another potential food source (albeit bitter 😉 )Cheers also for this great blog 🙂

Butter – what exactly is the tincture good for? Feel free to email me back (I think Ericka can forward you the address I think), it is fine with me (though, could you keep it private between yourselves? I have been pretty protective of it so as to avoid all the spam, identity theft, etc.) :).

THANKS!!

by His grace alone,

Jackie

this is a great article.. I eat a few of the lettuces.. as you say, they’re mostly too bitter.. so funny to me that almost all of our garden lettuces started closer to a thistle 🙂

The sap of wild lettuce contains “lettuce opium,” with pain relieving and sleep inducing effects. Although not an actual opiate, this is a powerful chemical that can be dangerous if too much is ingested. Just to be safe, it’s better to stick to using wild lettuce as a garnish green, a few leaves in a big mix of other greens. (The bitterness helps with that, anyway.)

Oh, and a link to what happens when you eat too much:

http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC3031874

Hi Beecloud, thanks for following up on your earlier comment with a link to a study. The study you linked regards a different species of wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa) than the one discussed in this post (Lactuca serriola). All Lactucas have some narcotic effect, but Lactuca virosa is the most potent, and it is rarely found in North America (Sam Thayer, personal communication). I am not recommending people eat Lactuca virosa, just those mentioned in the post, and particularly Lactuca serriola with which I have extensive first-hand experience and no ill effects to report.

You nonetheless make a good point for our readers who are not based in North America–that there exists one species in the Lactuca genus, found in Iran and likely surrounding regions, that can cause ill effects if eaten in excess.

Cheers

Do you have any experience cooking matured prickly lettuce leaves? Do you need to trim the prickles?

Hi Constance, I don’t have experience cooking mature prickly lettuce. I never tried it because they are so, so bitter! If I were to attempt it, I would trim the prickles. Best of luck and let us know what you find out!

Wonderful lots of herbs information for healthy living and wild foods. Love it.

I eat delicious wild lettuce-not prickly lettuce, which has a bad effect upon me-almost daily. Best way? In a smoothy with other veggies and fruits; the fruits will quell bitterness. But have also have blended leaves with nothing but lemon chunks and ginger, making what felt cooling, cleansing and in my opinion tasty. I only experience a general feeling of well being, never sleepiness or illness. And since money is tight I rely on wild lettuce as a vegetable source

Funny I just came across this article – I’ve let my yard grow undisturbed this year and it’s just FULL of wild lettuce (as well as something that looks like tarragon but isn’t and something that just has to be related to peas – still working IDing those). Thanks for the great information!

curious whether anyone has prepared an infusion (with vodka?) with young leaves; and if so, what your findings are.

Interesting article, thank you. Fairly new to San Diego, CA, my back yard this year is covered with mallow plants, which weren’t here last year, and only one separated and contained area has prickly lettuce. Isn’t that strange? Welll, should I just let these large prickly lettuce leaves die off in the summer or should I trim them back any? I’m allergic to latex gloves, would the latex you mention cause me any issues with this plant?

Hi Cindy, I doubt prickly lettuce sap should hurt you. Commercial latex comes from the rubber tree, a completely different genus. Trimming them back is up to you. If you want them to produce seed and come back, maybe leave a few to go to seed. Many people do not want them and therefore pull before they go to seed.

This may be off subject but after reading the comments felt this group might have the answer.

Does anyone have experience with composting prickly lettuce? Do the prickly parts breakdown? I hate to waste the material but don’t want them in my finished compost that may be used barehanded. Thank you.

Alan

Gosh, I don’t. I usually keep prickly stuff out of my compost too. Hopefully someone else chimes in.