My mother-in-law-to-be walked into our apartment and bee-lined it straight for Dina Falconi’s book, Foraging & Feasting: A Field Guide and Wild Food Cookbook (2013), which I had out on the coffee table. The cover is a hand-drawn festival of colorful wild plants, from bulbs to greens to flowers, bursting forth from a Dutch oven to dance on the crisp, white background.

It’s a hardcover book that really is quite lovely in the hand, so I could see why Nancy liked it. She collects and sells antique children’s books, many of which are fashioned with such quality. I love hardcover books with decorative end papers, and this book’s are fantastic—a whimsical, pink-red revelry of Alliums (field garlic, to be exact) drawn by Wendy Hollender, the botanical illustrator who teamed with Falconi on the project. The rest of the book is hewn with similar care, from the full-color botanical illustrations of 50 common edible plants with identification and usage information, to the recipe section that follows.

The seeds for Foraging & Feasting were planted a long time ago. Falconi recalls her earliest experiments in the culinary arts—sprouting grains and beans, and cultivating cashews into cream—in her family’s small railroad apartment in New York City. Later, at summer camp, she made the “life-altering and mind-blowing discovery” of wild mint, berries, and other wild-growing foods.

“For an inner city kid this was surreal—harvesting fresh, vibrant food directly from the earth rather than purchasing items viewed through store windows, separated by store walls, and owned by somebody else,” she writes.

She became enamored of the idea that she could connect with her forbears through food—both the early Americans who foraged for food, and her more recent ancestors, those of Jewish, Mexican, German, Mayan, Lituanian, Austro-Hungarian, and Italian descent. “As a lifelong cook, I have enjoyed creating and eating foods that my forbears may have eaten as a way to celebrate and honor them,” she said. “I guess you could call it soul-filling food, grounding food.”

Always, there were cookbooks. “Cookbooks are my soul food. I have loved and collected them most of my reading years. I fall asleep with them as bedtime stories,” she writes.

In time she became a devoted cook, gardener, clinical herbalist, and “serious forager.” Though she’d been envisioning the book for more than a decade—and compiling information for more than 30 years—it was not until Hollender moved to her town and agreed to the project that the work began in earnest.

“Wendy and I met through a mutual friend in the late summer at a neighborhood outdoor ‘pizza making and movie night’ party,” she said. “A few months later, I asked Wendy if she wanted to work on this book with me, and she said yes immediately.” After that it took four years to write, test the recipes, direct the art, and design the book. When it was near completion, they launched a campaign on the crowd-funding site, Kickstarter, and with the help of more than 2,300 backers, raised $115,000 to pay for production and printing costs. They quickly sold out of the first printing and ordered a second.

Plant Maps

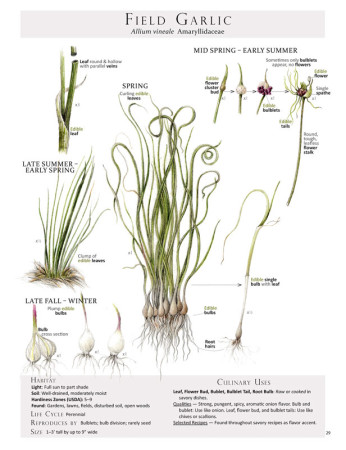

Hollender did the botanical illustrations—50 common edible wild plants painstakingly detailed in watercolor and colored pencil—that make up the bulk of the Plant Maps, so-called because they introduce the viewer to new plant territory.

These are as informative as they are lovely. The plants are illustrated in multiple seasons, and important characteristics are labeled with callouts. Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum), for example, is depicted as an edible seedling in “spring – fall”; a larger, pre-flowering plant with “edible leaves & tender stalks” in mid spring – summer; and a flowering plant with edible purple flowers and leaves in summer – fall. A turned leaf is labeled “leaf underside whitish, slightly fuzzy,” with another drawing of the same plant labeled with “opposite leaves” having “serrate margins (coarsely rounded to pointy teeth).”

Additional details about each plant are included in information boxes at the top and bottom of each page listing common and scientific names; habitat (USDA hardiness zone, soil, light, biome); life cycle (annual, biennial, perennial); manner of reproduction; size; culinary uses by plant part (whether to eat raw or cooked, along with preparation suggestions); flavor qualities like aromatic, sour, or musky; therapeutic uses where applicable, such as “digestive aid”; and page number references to recipes with which a given ingredient can be used. Colored circles alert readers to important information—red to indicate dangers or cautions, yellow to indicate similarly used species, and green for harvest and edibility information.

The Kitchen Arts

Falconi’s cookbook section, entitled The Kitchen Arts, uses a “master recipe” approach in which a wide range of ingredients can be used in a given recipe. There are more than 100 master recipes in the book, divided into chapters on Beverages; Relishes, Spreads and Condiments; Fruit Coulis and Syrups; Wild Salads; Wild Grape Leaves; Soup; Sandwiches; The Wild Eggery; Potherbs: Cooked Wild Vegetables; Animal Kingdom Entrees; Desserts; and Basic Cookery. The master recipes make thousands of recipes possible, because you can mix and match various ingredients—both wild and cultivated—to create the dishes, many of which can be adapted to accommodate dietary restrictions.

I personally find the concept appealing since I’m bound to doctor a recipe with what I have on hand anyway. Plus, you don’t have to find a specific wild plant in order to make a dish.

I came into a bounty of purslane (Portulaca oleracea), so I navigated to my recipe options using the index, which I like better than navigating from the monographs because the types of recipes are listed there. This led me to the Grain Salads Master Recipe. Falconi recommends using one or more of the following greens in the recipe: purslane, chickweed, dayflower, sweet cicely, sheep sorrel, wood sorrel, day lily shoots, garlic mustard, lamb’s quarter, and violet. I used purslane. The recipe also calls for an aromatic herb, from which you might choose lemon balm, gill-over-the-ground in flower, wild bergamot, spearmint, peppermint, apple mint, oregano, or some combination thereof. I used wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa). The grain choices are equally broad, and for that I used quinoa. There are also optional ingredients to add like feta cheese and whole beans. I ended up with a tasty cold salad of quinoa, purslane, wild bergamot, chives, lime, oil, salt and pepper, navy beans, and feta. My better half and I wrestled for the leftovers.

So many of the recipes in this book tickled my fancy, I couldn’t begin to list them all. But I am eager to try the water kefir sodas and mint lassi, the flower and herb butters, wild tapenade, mint salsa, herbal fish spreads, and fruit catsup. I’m racking my brain for local plants to use in the “Old-School Bouillon: Wildness Captured & Preserved in Sea Salt,” where you combine 16 ounces of minced plant matter with 4 ounces of sea salt, mix well, press and cap with plastic (so as not to corrode a metal lid) for future soups of countless wild flavor combinations. I appreciated being educated on the subtle differences between fruit syrups, coulis, cordials, succus, and glycerites; and of course I’m always excited about wild salads.

In Falconi’s salad tips, greens are broken down into five flavor categories to help you mix and match to your heart’s content—mild-flavored, sour-flavored, spicy or pungent, bitter-flavored, and aromatic. Likewise, the secret ingredients to making your salad dressing more pungent, creamy, or umami-savory, among others, are laid bare. The list goes on, reaching full-drool in the middle of the desserts chapter.

I think the culinary arts could become less of a mystery to me with Falconi’s book in hand. There’s even a chapter on Basic Cookery that includes healthful foundational techniques she recommends integrating into your cooking regimen—like how and why to soak your grains and beans, instructions for making animal and vegetable stocks, and culturing cream.

“The richness of a soup or sauce comes from homemade broth, or fond, and not a bouillon cube,” she writes. “The flavor of mint ice cream comes from fresh mint, not mint extract, and its creaminess from farm-fresh, pastured egg yolks and cream, not stabilizers and gum.”

To that end, she begins The Kitchen Arts with a discussion of ingredient sourcing, recommending against eating, for example, genetically modified (GMO) grains, or animal foods from animals raised in concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFO’s). In place of soy sauces made by hydrolysis, she recommends using traditionally fermented tamari made from soybeans and salt.

“Ecologically grown foods may be more difficult to locate and often more expensive,” she acknowledges. “Still, I encourage you to use them as much as you can. Your taste buds, your health, and the earth will thank you for it.” In writing the book, she challenged herself to translate recipes into healthier versions without sacrificing flavor, so most of the dishes call for “whole, unprocessed, organic ingredients free of artificial flavors, color, and chemicals.” She describes herself as “a strongly committed locavore” but not a purist, admitting enjoying treats like Celtic sea salt, spices, olive and coconut oil, and dark chocolate sustainably produced outside her foodshed.

“Harvesting food and cooking it into meals with basic wholesome ingredients produces a subtle but potent revolutionary effect: We re-instill our most obvious responsibility—self-care and self-empowerment,” she writes. Hence the recipe section, which “aims at rekindling the kitchen arts, empowering us to spin the weeds into glorious nourishment.”

She describes her own recipes as “frank and undisguised, like really satisfying peasant food that speaks of its terroir—reflecting the essence and quality of the soil, climate, and ingredients that make them up.”

Food as Medicine

Falconi is a clinical herbalist, which means she works with people to improve their health using food and herbs. “I am very happy to witness improvement in health of many folks when they change their diets for the better: when food is medicine,” she explained. “I have many interesting stories—like the one about my food mentor who cured himself of a terminal illness with food and herbs and outlived his doctor; or the man who was told he was infertile and now has two handsome sons; or the lady who no longer needed heart surgery: her arteries had been 85% clogged, but once cleared, the doctors claimed the initial diagnosis was a mistake.” And yet, she noted, “there is a lot more to healing than meets the eye.” She also pointed out that not everyone improves so dramatically.

While Foraging & Feasting is not a guide to clinical herbalism, Falconi infuses herbal wisdom into a couple areas of the book. At the bottom of the monographs there is a small header listing Qualities that includes nutrition information, and therapeutic uses when appropriate. Dandelions leaves, for example, are listed as “nutritive, bitter, high in beta carotene, vitamin C, calcium, iron,” and she notes: “leaf and root considered health tonic specifically for liver and digestion.”

The Beverages chapter includes a master recipe for Herbal Infusion Tea with recommendations for several compounds, or tea blends, good for particular uses. For example, there is a Winter Wellness Tea to support immune health containing lemon balm, elderberries, anise hyssop, burdock root, wild bergamot, and schizandra berries; and a bitter Spring & Fall Tonic: Nasty Good for liver and lymph, traditionally consumed during the change of season. A chart of Herbal Tea Flavors and Actions accompanies, allowing readers to make their own blends with both flavor and therapeutic uses in mind. Another master recipe for Therapeutic Spirits teaches how to make tinctures, which are common herbal medicine preparations, using some of the plants featured in the book.

Info Charts

Left-brained individuals may appreciate the series of charts at the book’s center. The Plant Biographies condense much of the information from the Plant Maps into a two-page glance showing taxonomy, life cycle, place of origin, and reproductive strategies for each of the featured plants. There is one for Plant Habitats/Growing Conditions, and another that is a generalized Season Harvest Chart, particularly suitable for the northeastern United States (Falconi is based in New York’s Hudson River Valley) but broad enough to be usable as a reference for other regions. Last is a condensed chart showing culinary uses for the 50 plants.

Foraging Arts

Falconi addresses foraging topics—from sustainability and safe foraging zones to timing the wild food harvest and tips for specific plant parts—in The Art of Foraging. I thought she tackled the sustainability question nicely in her Regenerative Harvesting Tips. Among them she advocates “conscious harvesting” by taking plant inventories and observing plant growth and reproduction. “With this knowledge we can encourage or control plants, depending on how they behave within the ecosystem,” she explains.

Many of the book’s plants are considered to be invasive species, and others are aggressive and prolific. If you decide there is reason to control a certain plant’s population, you can do it by harvesting and eating them. Likewise a less aggressive species can be fostered to promote plant diversity. In many cases, “our harvesting creates more abundance as many plants respond to pruning by branching out with vigorous new growth,” she explains. Examples include leafy plants like nettle, amaranth, and mint, harvested at the nodes. Conscious harvesting can actually help some species.

In another section, Assessing Land: Is It Clean Enough to Harvest From, she addresses the ongoing question about where to forage. It had not previously occurred to me that foraging near buildings might be risky business. “Unfortunately most building are constructed with toxic materials (pressure-treated lumber, paint, asphalt shingles, etc.) that leach into the surrounding soil and contaminate it,” she told me. In the book she writes: “While many foragers gather near roads and dwellings, seemingly at ease with taking risks, others will gather only from pristine areas. Personally, I like to harvest at least 20 feet away from buildings and small roads. If a road is large I move much farther away—maybe 50 feet. Each of us needs to find the land we feel comfortable harvesting from. I urge foragers to become land stewards who strive to keep land healthy and pollutant-free. Our harvest depends on it.”

Why Foraging?

“Many of nature’s beneficial plants are so abundant that agriculturalists consider them pests; even the average person sees these wonderful, useful wild plants as bothersome weeds,” laments Falconi, who hopes to change how people view plants.

“Considering the enormous toxic load that modern agriculture spews, foraging also offers a healthy way to eat without externalities, where all the costs are paid upfront. No hidden damage to the ecosystem from pesticides, herbicides, plastic packaging, or other pollutants. No monocultures, soil erosion, or carbon footprint from farm machinery or food transport,” she writes. “Foraging usually incurs very low food miles, and with foraging, no one is exploited in the social or economic sectors. Nobody is ripped off.”

Conscious foraging makes use of nature’s vast gifts, many of which are to be found right in our backyards. “The trick is to be able to see it, to train our vision to see beyond what we normally see so we can comprehend what actually has been there all along,” she writes.

“This is a gorgeous book in every way and may well be one of the best forager guides/cookbooks available. It’s certainly my new favorite,” writes the well-respected herbalist, Rosemary Gladstar, on a back-cover endorsement of Foraging & Feasting: A Field Guide and Wild Food Cookbook. Endorsements by Sally Fallon Morell, author of Nourishing Traditions, and fermentation guru Sandor Ellix Katz also dress the back cover.

Foraging and Feasting ties together a lot of good information about healthy eating and therapeutic herbs with a creative array of useful, tasty, and well-tested master recipes for wild and cultivated foods that, rather than limiting your wild food wanderings, encourage you to explore a wide world of wild-infused recipes. From the elegant writing to the handcrafted illustrations to the consciousness that underlies them, this book is a gem.

Find it at www.botanicalartspress.com.

*This story appeared in the August 2014 issue of the Wild Edible Notebook, available for just $2/month, including 6 issues when you sign up. The more signups there are, the more time I have to write and publish stuff here at the blog, as well as improve upon the Notebook. Thanks for your support!

Leave a Reply