It’s now a week into this month’s wild recipe challenge at Hunger & Thirst for Life, and can I just say, I’ve been out of it for eight months and all of a sudden, this game has gotten way harder.

This month, Wild Things is a “Tree Party,” which, despite the fact that it conjures up happy tree house imagery for me, is not as simple as it sounds, because the following tree parts are disqualified, reserved to grace a later contest on their own merits: leaves, needles, fruits, and nuts. So much for the pine nut vodka I was thinking I’d make into vodka sauce.

Instead we are left with “sap, bark (including cambium), pollen, catkins, and resin,” explains Butterpoweredbike, head cheese of the wild recipe share. She expects to receive monographs or recipes for herbal remedies that use tree bark, and syrup from folks who tap trees, in addition to her own culinary experiments with ponderosa pine bark.

One of my favorite wild food gurus, Sam Thayer, is a tree tapper. “I’m at this period of the year where I check the weather every day and try to guess if the sap will run soon, and when to start the big crazy period known as sap season,” he wrote just a few days ago (personal communication, 2013). “It’s a good way to come out of winter. Kind of like waking up in the morning to a fire alarm.”

Sap season. Sounds nice, fire alarm notwithstanding.

Meanwhile up here at 10,000 feet in the Colorado Rockies, I spent several blissful days maniacally chasing fresh tracks deep among the conifers on my snowboard, relishing my growing strength now that the desk job is nearly a month behind me. Then, a day later, the bright sun came out to melt rivers through the soft, wet ice on the pavement below our apartment.

Spring growth is still a ways off up here. To find it I will have to descend the hill, but not yet—as there is more snow to come, and I’ll be here waiting for it patiently when it does.

Black birch back when

Anyway, after Butter’s creative-arm twisting, I decided to try making some stuff for the recipe share from the half jar of black birch (Betula lenta) twigs I collected in Connecticut last summer.

Black birch brings back my childhood because it grows all around my parents’ house, and I used to pluck and chew the twigs all the time.

Steve Brill (1994) describes the tree as having “dark, smooth, shiny, largely non-peeling bark” in younger specimens, with “horizontal light-gray lenticels that look like dashes.” The leaves are oval, pointed, alternate, and stalked, 4-6 inches in length, bright green, and double-toothed, he explains. He also says there are no poisonous lookalikes.

For me, these identifying features help, but ultimately it’s the wintergreen scent in a broken twig that gives the tree away.

Euell Gibbons writes of black birch, also known as sweet birch, in Stalking the Wild Asparagus (1962), my first wild edible read. “The sap of the sweet birch is the pleasantest of the tree saps to drink, straight from the collecting pail,” he writes. “Don’t expect it to be strong-flavored; it tastes more like pure spring water than anything else, but it has a faint sweetness and a bare hint of wintergreen flavor and aroma.”

Back in the day I would read that chapter over and over, including his recipe for birch beer, and daydream—while lying on the driveway looking skyward, a birch twig in my mouth—of one day tapping birch trees. Alas, to this day I have yet to experience “sap season.”

Interestingly, the aroma in a broken birch branch comes from the same oil as wintergreen.

“For some reason, known only to Mother Nature,” these two unrelated plants yield an essential oil which is identical in both species,” Gibbons writes. The flavorful oils are volatile, both Gibbons and Brill write, such that boiling can ruin the flavor.

Black birch caramelized onions

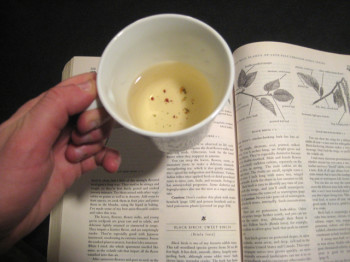

Since I had just a handful of twigs to work from, I took extra care to extract the flavor of the birch by pouring a small amount of very hot (but not boiling) water over the handful of branches, and then covered to let steep. This did not impart a strong flavor, in keeping with Gibbons’ description of the sap, so I reheated the tea several times, without boiling, and let steep longer. It was funny how strong and lovely the aroma came out despite the mildness of the tea.

“Can you taste the flavor?” I asked Gregg, delivering him a spoonful.

“Yes, I can taste it.”

“I’m afraid I’ll lose the flavor if I prepare it how I was planning,” I said.

“You won’t lose the flavor,” he assured me, his eyes trained on the computer screen.

So I sautéed some sliced onions in oil until they started to caramelize a little, then splashed in the birch tea bit by bit, heating but not scalding, along with the slightest drizzle of molasses.

“Can you taste it?” I asked Gregg, after he finally got the slippery onion piece into his mouth that I first dropped onto his face by accident, whereupon it slid down and landed in his hand.

“It tastes like onion,” he said.

“That’s it?”

“Well onion is very strong.”

So much for not losing the flavor. I stomped into the kitchen. “I only have one batch of birch sticks and now I can’ make anything with it!” I grumped, before adding another splash of the tea and searing the onions once and for all.

They were just meant as a side dish anyway, served together with breaded and baked venison cutlets, mashed potatoes, and a gravy of Suillus brevipes mushrooms, butter, and wild garlic. (The gravy came out rather gooey for my taste, despite my recent efforts to champion the slippery mushroom.)

“Wow, this is gourmet,” Gregg enthused, diving in. And later: “You know I think I can taste that birch flavor when I eat the onions with the venison.” Sure you can, guy.

But honestly I did feel like I could detect a hint of the wintergreen flavor in them. At the very least, the aroma wafted to my nostrils from each tasty forkful—so I’m calling it a recipe, though next time I’ll probably triple the twigs to see how it works out.

If not, there’s always salad dressing. Or toothpaste, for that matter.

Leave a Reply